The Frogs At Steepletop

It was the death of the poet Mary Oliver a few weeks ago that put me in mind to write about what I saw at Steepletop, the home of Edna St Vincent Millay in Austerlitz, New York in the Berkshire Hills. Or more precisely it was the frogs that I wanted to bring up. It was a hot and still and gloriously full August Sunday afternoon in 2017. We had been shown around the poet’s book and memorabilia-crowded house and had walked up the slope through the gardens to the spacious meadow brim and followed the trail which cut into the woods.

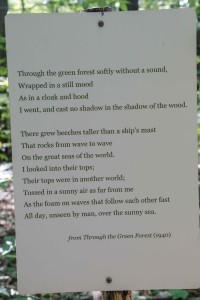

A half dozen of Edna’s poems lined the dappled path leading to the quiet grave site.

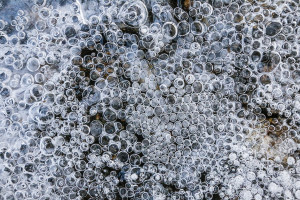

After paying our respects we returned to the house and decided to take a look at the formal garden aside it. There was a deep sunken pool full of green murk with a log floating on top. A casual glance would have perhaps only noted neglect. But then we spotted one frog and then another and still more. It was a large wonderful colony. Everything was all remarkably still, no sudden Basho splash of significance.

With a 400 mm lens I could probe down into the pool, enjoying the clusters and line-ups and visual relationships of the dozens of frogs below. It was all so peaceful; the frogs simply there, just alert and relaxing.

It was a moment Edna or Mary might have woven into some revelation. We backed away slowly with a bowed sense of gratitude, not wanting to create a disturbance or splash of any kind.

The Haystacks of Romania

Years ago on a visit to the Chicago Art Institute, I was transfixed by Monet’s haystack paintings. I was captivated by the notion that Monet conveys so well that light itself could be a pure spiritual revelation. That light throughout the day could evoke a range of powerful emotions and meditations was an awakening for me at that time and this deepened both my sensitivity to art and to the possibilities of photography. Early morning light is not like the light of 10 o’clock, the light of noon, the light of late afternoon and evening. And with each season light takes on different tones and vibrates within us on different levels of resonance. Monet conveys this as few others and it is his concentration on one motif that shows us the mysterious workings of nature in its subtle gradations. Every picture, though compositionally the same, is charged with difference, with vital uniqueness. In short, an infinity of perspectives and of palette can open up in common sights. I had never seen this so clearly depicted before nor felt it so vividly. The haystacks themselves were an extra bonus, their lovely curved shapes, their weight, their presence, their own message of time. What I hadn’t realized then was that Monet’s haystacks were an endangered species and very rapidly disappearing in the western world. The year was 1983 and I drove from Chicago to Santa Cruz, California much of the way on rural roads and I did not see one haystack such as those Monet (and for that matter Millet, Van Gogh, Breughel and countless others) had painted. On several trips to France in the late 1980s, I was struck by the fact that the lovely, wide and rounded conical haystacks were a thing of the past. Mechanization and efficiency had seen to that. Round bales of hay wrapped in plastic or massive walls of hay had become the de facto sight all over.

These remarks are preface to the glorious experience I had in October 2017 in the Maramures area of Romania just south of Ukraine. The hilly region is synonymous with an aesthetic loyalty to folkloric ways. Along with traditional arts and architecture, Monet-style haystacks were everywhere.

It would be no small thing to say I was completely enthralled and set about capturing them in all the settings I could. In many ways I had strayed into the late nineteenth century, into Monet’s rural landscape.

There were clusters of magnificent haystack specimens surrounding the small guest house where I was staying in Desesti. I spent hours one morning studying them as an overnight frost thawed and released a softening humidity into the air. And there was the additional touch of so many tall narrow wooden steeples!

I continued to find and photograph traditional haystacks in Bukovina and Transylvania regions but for me there was nothing like the first impression when I drove down the steep twisty road on the high wooded ridge that divides the Maramures region south to north and into the lovely Mara valley where all of these photographs were taken.

One Single Bright Leaf

Fall foliage time is here again in Vermont. Thousands of visitors have descended from all over the world to enjoy the celebrated wonders of this dazzling season with its intense bright reds and oranges, hill and mountains slopes like rainbow quilts and tapestries of fire.

I have photographed these displays so many times and never fail to find great pleasure in the act. But a disciplined photographer is always looking for a new perspective, a different way of treating a known subject, perhaps just searching for a fresh vital symbol. I took scores of pictures in recent weeks, climbing through thick woodlands to rocky summits, circumambulating pools and lakes.

I drove hundreds of miles to new trails and parts of the state I had not yet explored. I was pleased with many pictures, but in the end, there was one that I liked best. I took it on my own land, in the 4-acre meditation park I’ve been working on for nearly thirty years. I was using my long 100-400 zoom and probing into the thickets so as not to disturb webs. One bright patch of color caught my eye, a single solitary illuminated leaf.

The next day I wrote this haiku:

only the one bright

yellow leaf that hangs

in the dark forest

Motion and Color Streams

Wind-tossed flowers and bushes have always fascinated me—the streams of charged color photons, the morphing acrobatics of flung and dissolving colors, the wild interlacings and interweavings along the spectrum. Breezes and winds are almost always blowing. Gardens are rarely still. Much of what we see is always a blur and yet we hold in our minds a kind of Platonic ideal of things, a non-changing form, be it of a flower, a garden, a place, a moment, even a river! It is as though things exist for us as solid architecture. The unpredictable wildness of streaming traffic we rarely remember as the jumpy pulsing fluctuating ribbon that it was. As a photographer I’ve been studying motion for years, taking exposures of varying length, experimenting constantly, sometimes being still and registering long seconds, sometimes panning, zooming, dancing with the motion itself, producing contrapuntal rhythms, sometimes harmonious, sometimes not. Recently I was in the Scottish Highlands where a large patch of bright orange crocosmia (Crocosmia Masoniorum) was growing on a cliff with the choppy water of the Loch Ewe beyond. There was a stiff and unsteady breeze and the flowers were tossing about joyfully, at times deliriously. How to capture the charged atmosphere, the orange, greens, blues swirling together, entangling and pouring forth? I took a number of shots: first, I froze the motion to give a sense of the place.

And then I did all the things I’ve described that I usually do, slow and fast, the dancing with my camera.

And then later just out of curiosity, in my Photoshop laboratory, I played with mirrors and fused images. Here is the one I like best.

(Take a look in the Recent Work picture gallery for a detailed view.) It’s got all the charge and wonder I was feeling at the time, and the suggestions and symbolic intimations that make the mirror-verse so captivating.

Romania – A Photographic Journey Along the Carpathian Arc

(This is the statement for my September 2018 exhibition at the Crowell Gallery in Newfane, Vermont)

In October 2017, I traveled alone along the Carpathian mountains in the north of Romania near the border of Ukraine and then southward through Moldavia down the spine of the country to the great east-west wall of the Transylvanian Alps. The astute observer and political-travel writer Robert D. Kaplan sees Romania as “a wondrous geographic confection… the ultimate marchland, a vast territory hacked to pieces by invading armies, and constituting the frontier extremities of the Byzantine, Ottoman, Habsburg, and Russian Empires, even as the language itself signaled a longing for the Latin West.” For me, it was an inspiring odyssey through striking landscapes bearing many signs of a rebirth after a long period of historical turbulence. I was happy to witness a Romania beginning to prosper, its memories of the twentieth century’s vicious wars and grim Communist oppression ebbing away. I encountered a proud, skilled, resilient, and beautiful rural culture with a noticeably vibrant spiritual dimension. Agriculture in the mountain areas was still a traditional enterprise, with much of the work being done by hand and with the aid of animals. Shapely evocative haystacks—the features of European painting for ages and now completely vanished in the west—were everywhere. Monastic religion too was thriving with dozens of large religious centers, the majority run by women, beautifully restored and maintained and with sparkling newer satellite centers close by. Orthodoxy revels in painting both inside and out and to anyone involved in the visual arts the effect is mesmerizing. The three dozen images I have selected are an attempt to showcase all these characteristics. Landscape, people, art, craft, architecture, history, and a sense of spirit, both real and imagined, constitute the subjects of this exhibition.

A word about the fantastical images here is in order. For the last three years I have been exploring symmetry in my creative (as opposed to journalistic/realist) work. The world of mirrors has been particularly intriguing with its rich seams of unexpected forms and the sheer satisfaction that improbable balance opens in the mind. In these works on display, some of them printed on metal, I have tried to convey the mystery and delight of first encounters and discovery and also of dreams. My nod to Dracula is another story: initially I swore I would steer clear of this myth, but, like nearly everyone, I fell under its sway and gave in to the many requests for an image of the Count’s fearful lair. “Blood Castle” is the result of bringing energy to an originally bland image of Bran Castle, coaxing from it all the macabre pleasure I could muster.

January Ice

We have returned from Andalusia and my mind is still full of bright oranges and dark green leaves and rows of olive trees snaking across miles of meticulously textured landscapes. Stopping in an olive grove (or sometimes in a public park in a small town or village) for a picnic had honestly brought me keener pleasure than The Alhambra ever could.

On our last day in the countryside outside of Jimera de Libar not far from Ronda, we sat in the shade under twisty old trees, breathing soft sweet air and watching butterflies, and now here I was again in frozen Vermont. I might have found the contrast something of a challenge if I concentrated on the stricken, color-drained look of town streets and potholed roads and dwelt on the discomforts of drafts and slush.

Instead I was finding it exhilarating. Weeks of freezing temperatures with occasional thaws had completely renewed the crystal worlds of the two streams I was devoted to studying. Places I had photographed in December had been cleared away and reconfigured. Wide pools full of flat angulated ice mosaic had been transformed by the constant action of the flowing water and shifting temperatures. Over the dark rushing water planes and banks of variegated layers had reached out, grown, and been repeatedly cut away. In places there were three layers of ice, the topmost being dense and white and compacted near the edges and in the center where the current rushed strongest, lace like delicate crystalline fingers stuck out, leaf or frond-like and wafer thin.

In the pockets and coves of pools, ripples had frozen into sinuous irregularly spaced parallels. There were clusters of stilled bubbles, and sheets full of wrinkles where light and dark fanned over the surface pocked with burst bubble craters sometimes, the whole reflecting the trees and branches far above. And there were mottled surfaces where snow and water had mixed and refrozen and when stray light beams fell, patterns nearly invisible would glow. Just before Xmas, in the shop at Salisbury Cathedral I had bought a slender book called “Li, Dynamic Forms in Nature” by David Wade. It was a mini-guide to the dozens of patterns natural forces create. It had wonderful sketches of formations and for me an entirely new precise vocabulary and I was happy to be able to start using it to deepen my observations and appreciation here in the crystal galleries in what I was starting to think of as my private Louvre or Sistine Chapel. And so it didn’t prove that difficult to readjust to the stark and frozen world after the sensuous ease of southern Spain. Part of the adjustment was in the focus itself (isn’t it always?). And I had endless patterns to discover and photograph and in studying the photographs many occasions to keep the wonder strong.

***

December Ice

I love it when it becomes very cold in December and the snow holds off and the streams freeze. Just beyond my land there is a ravine that gets fairly deep. It turns and twists, dropping gradually down, and is filled with innumerable rocks, cascades, small pools, and dams composed of small branches and leaves.

Freezing temperatures create the most delicate works of ice art. Bubbles and ripples freeze. Crystals grow and fracture. Eddies solidify into astonishing traceries. Ice adheres to twigs like wax to candle-dipping wicks. Within a quarter mile the variety of ice forms can defy reckoning. For a photographer it is endless delight. I had been observing the developing of the ice for days as the temperature plunged sometimes going into the teens at night, but usually hadn’t brought my camera along. When I checked the forecast to find that snow was imminent, I decided to spend a few hours appreciating the wonders, knowing that in a short time all trace of the marvels would be gone, never to appear again in the same way. I worked until the light which trickles down into the small canyon through the pines, and bare maples and beeches, faded and my fingers became numb from the cold. Here are a few of many very satisfying images.

*****

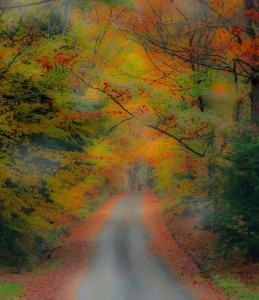

Through A Windshield, Wetly

Remote South Pond in Marlboro is a place I enjoy walking and photographing in every season except perhaps summer when it can get crowded with swimmers, kayakers, and fishermen. In the other seasons it is often completely empty of bustle. On only the windiest or busiest days is its surface ever much ruffled and so it is a wonderful glass, mirroring the many trees and low hills that surround it, the sky and the passing clouds. I had been to the pond every week since the start of Fall and had been documenting the subtle and spectacular changes of October. But on this particular day, the clouds kept dropping lower until mist turned to drizzle and then outright rain. I parked my car and began to walk along the shore, thinking the hood on my camera would protect the lens, but sudden strong gusts splattered the views and I was repeatedly cleaning the camera with a cloth. I returned to the car and proceeded slowly on the narrow dirt road that leads to and away from the pond. The brilliant colors and a lovely bend in the road prompted me to stop. I watched the water stream down the windshield and my breath added a soft spreading unsharpening to the scene beyond. It was all marvelous, I saw, a tableau shifting slowly from impressionism to expressionism.

I took a series of pictures and when I was satisfied, drove off and turned right onto one of my favorite roads, the wonderfully named “Cowpath 40.” Since there was no traffic I slowed way down. Every mile or so, I would stop and take pictures through the windshield. It became a gratifying journey home. Normally it takes only fifteen minutes, but this afternoon, it took over an hour.

The last picture I took through the windshield was of a farm and homestead next to the beautiful organic Lilac Ridge farm. Later I used a Dry Brush filter on the image to bring out a more traditional painterly quality.

***

Summer Webs

It was a perfect summer for photographing spiderwebs in the parkland I’ve created behind my home. Before this summer I had a rather blundering approach, using a macro lens and trying to get up as close as possible. What happened is that when I saw a web illuminated and tried getting in to photograph, I inadvertently destroyed so many other delicate masterpieces. The poem that follows is about such an experience although I was not trying to photograph when the experience occurred but only walking around and musing.

What made this summer so excellent was that there was always a certain amount of hazy humidity in the morning which in the early fall became a mist that stayed close to the ground. Easterly light filters through the woodland of tall mixed trees and lights up the myriad webs. This year was the first summer I noticed just how many webs there were on the land—thousands, tens of thousands: orb webs, parabolas, and uncountable tiny “tents” on the ground. The light and the humidity made them glisten and as I slowed down and spent more time looking carefully, I realized how extraordinary the spider presence actually was. The key to photographing was switching to a long telephoto lens. I used a 100-400 zoom and was often at the maximum. And so I could probe into the tangled understory without disturbing the dense delicate ubiquitous architecture. I could see so much more than I’d ever imagined was even there.

Here is the poem and here are a few of the images.

Apologies to a Spider

Despite trying my best to be mindful this morning

While out slowly walking in my woodland park

I snipped a spider’s filament and then glanced back to see

A wavering delicate silver masterpiece collapsing

into simply a tattered ragged line, nondescript

until out from it darted the builder, the spider master,

weaver, dream arranger, nightmare knitter, fly deceiver

rapidly scaling a thin thread and blending in with the bark

of the tree that rose sixty feet more into the high canopy

silvery with mist and interlace and distractions to my mind

until I thought of Whitman’s famous line “noiseless patient spider”

and returned to the original image and my careless deed

that ruptured the magnificent work of an artful, clever crafty being.

I wondered if the spider swore and cursed about what I had done?

What would have spilled out from my mouth if one of my works

had been so utterly wrecked? Could I have ever been so graceful?

So forgiving? So absorbed in the present? So happily unable to hold a grudge?

I can be irked by the presence of a moth and provoked to shout

Or groan petulantly if the electricity fails, the printer jams, the ink runs out,

And the spider just gets back to work, weaving, weaving, something marvelous.

9.9.2016

******

Riverside Cemetery

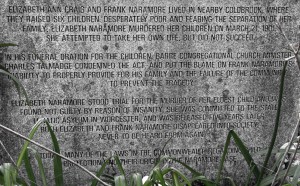

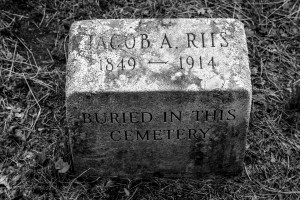

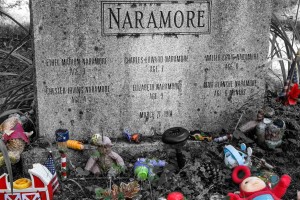

I visited Riverside Cemetery in Barre, Massachusetts in late August. An old friend had written me a few months before that it was where Jacob Riis was buried. Riis is such a revered figure among photographers and writers. His reformist zeal is in great need today, I was thinking, in our celebrity-obsessed society with its yawning income and opportunity gulfs. The cemetery is a few miles from the town center down a rural road and then about a mile on a dirt road in the woods and then still further down another narrow track. It is a remote and forgotten place. There is a wooden archway over the entrance with the name of the cemetery, and just to the left, a small stone marker indicates that this is where Riis is buried. His grave inside is unmarked. I passed under the arch and walked up the knoll to where most of the graves are. Old cemeteries are fascinating for the style of the headstones, the carvings and inscriptions. I headed for the oldest stones and spent time deciphering worn epitaphs and wondering about diseases and accidents. I looked for revolutionary war veterans, and then studied the obelisks, signs of nineteenth-century pomp and prosperity. I moved on to a newer section with stones that have the signs of our times on them—a motorcycle, tools of a workman’s trade, a love of sports, and one that was simply a rough-hewn granite bird bath, a wonderful touch, I thought. Beyond the trees the ground sloped away and I noticed a headstone in the shadows near a second, obscured gateway. I followed a path down to have a look, curious to see if I could find out why this grave was set so completely apart from the others above. The stone was new and had the names of six children on it aged six months to nine years. There were dozens of offerings all around, action figures, toy cars, trucks, dolls and stuffed animals. I wondered if the children had been the victims of a terrible fire. Then I went around to the other side of the monument and there was the wrenching story of the murder of the Naramore children in 1901 at the hands of their own mother. I was chocked up by the thought of the event and felt the pensive heaviness and anguish that come over you when you try to comprehend how something like this could have happened, how anyone could be driven to such an act, the awful mayhem, the cries of the innocent. The words on the stone mention poverty and the failure of the community, themes so close to the spirit of Riis’s work, and it seemed poignant that here in death in this lost place were the remains of these sad children along with those of the great reformer.

*******

I wrote this piece ten years ago. I came across it recently and decided that I still like it.

Savoring the Obscure

I was traveling this summer in France and Belgium as a stock photographer, that is, I was there to take lots of photos (stock), upbeat, attractive, marketable images. In many ways like a tourist, a stock photographer goes to the major sights, the big-draws, and does his best to show a place in its cheerful, most alluring aspect, to capture the sunny face of a thing, and weather-permitting, get the required blue-sky backdrop behind it all. So there I was at the start of the trip in Paris around the Louvre’s glass pyramid jostling with the crowds, clicking away with the hundreds of others. I went up to the roof of the Samaritaine Department Store for the lovely views, walked along the Left Bank to Notre Dame, wandered the crowded Latin (shouldn’t it be Greek?) quarter, strolled in the Jardin du Luxembourg, and plunged into the lanes and markets and cafés of St-Germain-des-Prés, all the time shooting away, pleased at the clinking sound of another finished roll of film landing in the bottom of my pack.

On each of the four days I was in Paris, there had always been times when I had wandered out of the popular fray, beyond the established sights, to places where the press and fever had fallen away and the decibels hushed. It had always seemed like the crossing of a boundary into a more peaceable kingdom. I had savored these times—whether in a modest, bare café in the Val du Grace with all the clients glued to the TV for the World Cup or the empty square at the side of St. Sulpice in the late evening when the sound of the fountain and the rustling of leaves were more audible than traffic and voices, or the discovery of the long linear garden atop the old viaduct not far from the Gare du Lyon. And then there was the deserted Parc de la Villette in the rain—these were some of the first joys that I was to experience repeatedly during the 6 weeks of my journey. I grew to understand that what I really treasured was not the grand, the imposing, the top-draw, but small, low-key, unsung things often too elusive to photograph. In other words, the obscure, the unheralded, the things guidebooks don’t mention and all the tours miss. These occupied a kind of parallel universe consisting of small islands of repose or unexpected oases. They were not only a balance but a completely alternative reality.

I shouldn’t have been surprised. After more than 25 years of travel I knew that the memories I reveled in most happened not to be what was usually considered major. It wasn’t a thronged Riviera beach scene I recalled fondly on a bleak winter’s evening, but rather an unknown and empty stretch of white sand on Cat Island in the Bahamas. And it wasn’t a palatial room at the Grand Hotel that filled me with longing but the simple lodging in the farmhouse of an old couple in the Dordogne, or, simpler still, my own tent-site in a near empty campground on the banks of the river Creuse under tall poplars, fish breaking the surface of the dark water, bats at twilight flicking about. Obscurity, rich obscurity. Delicious! Clearly there is something wonderful about having a place to yourself, something that is yours, not everybody’s, but what I felt had no escapist selfishness or conceit in it at all but more a sense of privilege. Gratitude not pride was the dominant emotion.

Right at the start of the trip was an experience that seemed to summarize these ideas. According to my original timetable I was to have gone on to Giverny from the village of La Roche Guyon where I’d spent my first night out of Paris. A few hours in Monet’s famous garden was my intention and then south to Chartres. But the weather was gloomy—dark threatening clouds sailed up the Seine in the morning. As a photographer I know that where gardens are concerned sunless conditions are usually preferable to bright contrasty ones, but so far this day had little luminosity and it had begun to drizzle. So I decided on another course of action—I would spend another night at La Roche Guyon. This was no difficult choice really—it was an atmospheric place and I had a simple room in the back of a B&B with a high window that overlooked a succession of green fields with the Seine a little more than a quarter mile away. In fact, my room and its view were so pleasant that I had put aside all thoughts of a restaurant the evening before and had bought bread, cheese, tomatoes, fruit and a bottle of wine and sat at my own table with the window wide open and the fresh cool air streaming in. It was a living impressionist world with the occasional barge going upstream and the call of the cuckoo coming from the hedgerows. As evening came on, it grew cool and I had to put on a jacket and then later wrap myself in a blanket from the bed, but nothing could pull me away from the view, not anyway until it grew too dark.

The prospect of another such evening softened my initial disappointment with my thwarted agenda but what to do with the whole long day? Checking my detailed map, I noticed to the north that the region was dotted with ruins and prehistoric sites. After driving out of Paris and along the Seine the day before it was a pleasure finally to be on less-traveled roads. That itself was enough to immediately redeem the day. The country roads wound up and down hills, in and out of woodlands, through fields where red poppies grew in the greenish wheat. The day had grown brighter and grand puffy clouds sailed overhead. Ah, Monet lives indeed!, I thought, setting up my tripod on a grassy verge. Up the road on a cone-shaped hill I came across a ruined medieval tower with fragrant elderflower bushes growing in the steep brambly moat. And just past the hamlet of Aveny, there was a sign for an “Allée Couverte” (indicated on the map like a table). I was curious as to what a “covered alley” could be. Parking was simply on a tilted grassy bank aside the road. It was not a frequently-visited site: evidently no buses or groups came out here. A narrow path led aside a field and up into woodland. The ground was stony, wet and slippery. I walked uphill for fifteen minutes, taking a few turns at trail junctions. The path leveled out on a shelf covered with deciduous trees. The Allée Couverte was a sunken Neolithic burial chamber: two walls of stone about eight feet across covered with three large slabs, two of them in place but the third awry, caved in. To my surprise, the sun had come out and the trees moved in a breeze and a dappled light flickered everywhere. There was a sense of ancientness and isolation in this hushed place but also a curious welcoming presence. I became very happy. A wonderful feeling of well-being flowed around and through me. Fragments of light shifted and flashed under the forest cover, a magic in itself, and I was simply glad to be there, glad to be present at this spectacle. I stretched and breathed long and deeply, and carried along by the exuberance of the moment, I actually embraced a tree and then, at the edge of where the land fell steeply, shouted “thanks” to the earth, the spirits, to the splendid energizing nowhere where I was. Then I remembered similar experiences I had had in other places—in a forgotten mossy temple in the highlands of Bali; in the Australian outback on a fissured mesa amidst rock outcrops; on a footpath in Shropshire over a hill of eroded crags. All these moments were connected and I realized I wouldn’t have traded this obscure wooded ridge-top for anything, not for Versailles or Chambord or St. Peter’s, or any popular place. I realized keenly that one of the things I loved most about travel was simply the unpredictable delight of the obscure.

Heading to the big sights is, in some ways, an excuse to really find something else. What most of us want, I suspect, is not to stand in a throng and stare at something prescribed and utterly known and public, but to find some unique personal delight. I have an uncle who would make frequent trips to Europe mostly going to the major destinations. Yet what I remember was not his rhapsodizing about the Coliseum or Piccadilly or the Prado or the Palais des Papes. He would always begin his happiest accounts in the same way: “And then we found this quiet little place…..”